“Liberté, égalité, fraternité!”

Liberty, equality, brotherhood.

These are the words under which Maximilien de Robespierre rallied the French revolutionaries in a speech he delivered in 1790 as they gathered to decide how to run their new society.

Robespierre was a key member of the Third Estate, a body of politicians and noblemen whom were supposed to represent the “common man” of France, but whom The Rest of History describes as “upwardly mobile winners; people who actually are not very representative of the mass of the French people, but people who are incredibly articulate and ambitious, and resentful of those above them.”

After decades of economic mismanagement, France under Louis XVI approached bankruptcy as a result of nearly insurmountable national debt. The administration had tried to resolve the debt by invoking restrictions on consumption and implementing higher taxes, but then a series of unprecedented climatic events devastated the wheat harvest and ushered in one of the most brutal winters in France’s memory.

Working people starved, struggled, and froze in their homes, and found themselves having nearly no choice but to resort to crime in order to survive.

Working people stole food, refused to pay their taxes, and broke property and hunting laws in order to feed themselves and their families.

Working people defaulted on personal debts and failed to pay required tributes because they simply no longer had the resources to spare, and as a result they were evicted from their homes and punished by the courts.

Rage built as the working people experienced a torrent of suffering, exploitation, neglect, and abuse, and were often blamed for their own misfortunes, characterized as deplorable, stupid, and morally inferior to the ruling elites.

The Third Estate became the tip of the spear for a populist movement which claimed to represent the “Will of the People,” but which, ironically enough, featured no working commoners in its assembly, and was instead led predominantly by lawyers, judges, magistrates, and other members of the bureaucratic middle management class.

Well educated in the oratorial style of classic Roman politicians and masters of rhetoric and words, these members of the Third Estate made bold declarations and rousing speeches to harness the anger and disenchantment of the working French and weaponized it against their political superiors in the administrative body.

However, this anger was a powder keg.

The Third Estate wielded the “Will of the People” against their foes, threatening violence and vengeance as retributions for decades of wrongs unless the administration caved to their demands.

The more the Third Estate worked to whip up anger in the French people, the larger and more threatening their ultimate weapon became.

However, it also became impossible to control.

Frustration and hate turned into open violence in the street.

A bloody riot: The Day of the Tiles in 1788

More bloody riots: The Réveillon Riots in 1789

A bloody revolt: The Storming of the Bastille in 1789

Armed, violent mass hysteria: The Great Fear of 1789

Extrajudicial killings of political prisoners: The September Massacres of 1792

The violence and instability allowed the Third Estate to seize power, but an internal power vacuum emerged as different factions struggled for dominance so that they could reform the government according to their own preferences.

The only thing that unified them was their hatred of those they had deemed their oppressors.

This culminated finally in the bloodiest period of the revolution, known as the Reign of Terror, lead, ironically, by the Committee of Public Safety, which oversaw the imprisonment and execution of more than 16,000 people, plus the execution without trial of an additional 10,000 to 12,000 people, plus the deaths of an additional 10,000 people who died in torturous prison conditions, totaling nearly 40,000 brutal deaths of political prisoners and figures deemed “enemies of the revolution” over the span of approximately one year (1793-1794).

Maximilien de Robespierre was one of the primary driving forces of this torrent of blood and violence, which he described as a necessary instrument of justice:

“If the basis of popular government in peacetime is virtue, the basis of popular government during a revolution is both virtue and terror; virtue, without which terror is baneful; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing more than speedy, severe and inflexible justice; it is thus an emanation of virtue; it is less a principle in itself, than a consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing needs of the homeland.” — Maximilien de Robespierre (emphasis mine)

This rhetoric set a precedent: in the name of Liberty, Equality, and Brotherhood, the imprisonment and murder of oppressors is Justice.

So, why does all of this matter?

Because it is happening again.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Luigi Mangione, known as the assassin who murdered UHC CEO Brian Thompson in the street, has been elevated as a folk hero in what seems to be just a new development in a rising acceptance of political violence as an essential tool to advance the “Will of the People.”

While it started as a meme, the concept of “Eat the Rich” has begun to catch fire, and the idea of destroying “oppressors” and consuming what they leave behind now officially has mainstream appeal, spreading like wildfire despite all attempts by prominent media figures and politicians to control the blaze.

The harsh truth is that many working people are starting to find themselves in situations where no matter whether they work full time or not at all, they’ll still struggle to get food, pay bills, etc — and possibly even face eviction, wage garnishment, etc.

Even worse, they feel like they have no representation in the halls of power, and no way but violence to make their voices heard.

When working isn’t enough to get by, and cries for help fall on deaf ears, it becomes more difficult for workers to justify participating in and producing for the society, and that’s when things begin to unravel.

Inflation is a short term pacifying solution for this, but using it is like digging a pit under the castle’s foundation to get the resources to make more bricks for the structure — it’s only a matter of time before the whole thing collapses.

Employment and entrepreneurship are important parts of the solution, because they are the mechanisms through which the capital class returns money to circulation by purchasing labor from the working class.

People need vocations — not only to help them earn money, but to keep them busy and to give them something they can take pride in: the positive impact of their labor on their community.

People enjoy feeling useful to their community. People also have a deep need to feel secure, and a desire to climb the social hierarchy as a result of their knowledge, skills, and labor.

When these needs are not met by a society, people tear it down and rebuild, because that at least allows them to contribute to something and climb some kind of social ladder, even if the structure is a shadow of the one they rebel against.

This a deep seated attribute of human consciousness captured most aptly in the Satan character of Paradise Lost, who states: “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

People want power more than they want comfort, and that’s why bread and circuses in absence of seats in the halls of power always eventually fail to pacify.

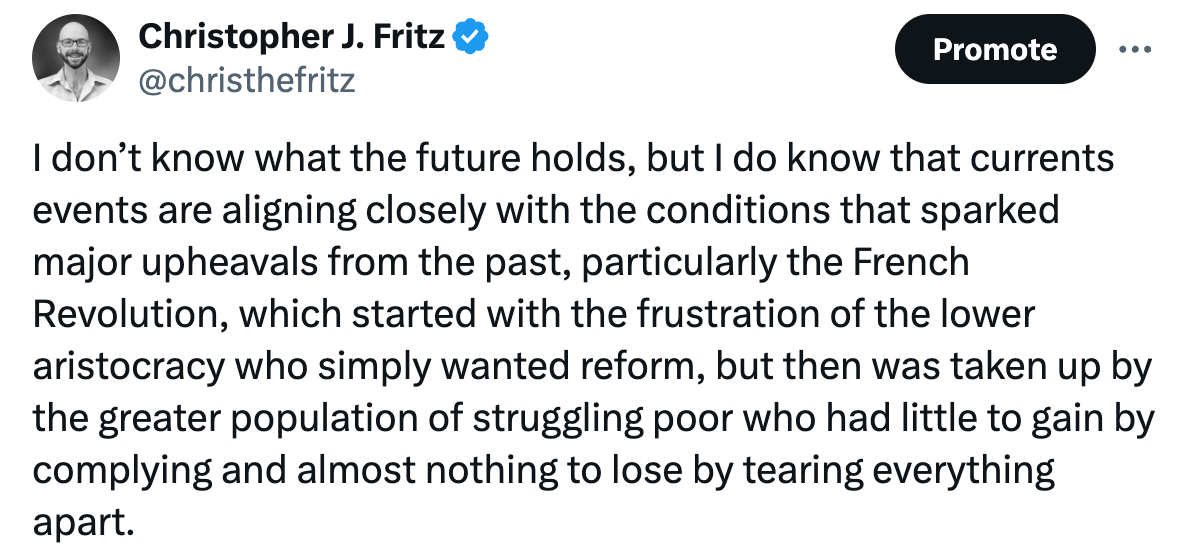

Recent attacks on leaders in the private and public sectors are merely warning shots of a seething tide of rage similar to what sparked the French Revolution.

The only path to peace is the real empowerment of the working class by inviting them to the halls of power — something the French leadership refused to do in 1789, which ended up leading to an outbreak of chaotic Hell at the heart of civilized society.

Bureaucracy only works as a cloak to disguise the machinery of power as long as the working class doesn’t set it on fire. But once the common people light one corner, it’s only a matter of time until the entire machine is consumed by the blaze.

History is violence, and the next 10 years may be our final chance to avoid repeating it.

Upgrade To Paid

Support my work and unlock free ebooks, exclusive content, community perks, and my full post archive for only $5 per month. That’s cheaper than a decent beer, a nice coffee, or a fancy candy bar, and it lasts way longer.

X Highlights

What I’m Working On This Week

In ancient times, one of the core disputes between the Stoics and the Epicureans was about how involved people should be in “public life,” which basically meant politics, business, and civil society.

Epicureans elevated Happiness as the greatest good, and argued that participating in public life was one of the best ways to destroy personal happiness and contentment, because it required one to take responsibility for the well-being of others whom they could not directly control, to make often painful sacrifices in service of lofty ideals, and to face fierce political rivalries that led to much trouble and sometimes even death.

Stoics elevated Virtue as the greatest good, and argued that among the core marks of Virtue were those very things that the Epicureans believed were important to avoid in order to preserve Happiness.

To pursue Virtue often requires one to sacrifice Happiness.

To pursue Happiness often requires one to sacrifice Virtue.

For the last several years, I have stood on the fence of these two ideals.

But recently, Socrates’s sentiment has weighed heavily on my mind: those who refuse to step up as leaders in the public sphere end up ruled by people worse than themselves.

While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I have the makings of a great leader, I also know that simply “waiting on the world to change” is not only ineffective, but irresponsible.

And so I am seeking to increase my knowledge and skills so that I might personally be of greater service to the greater public.

I need knowledge to understand the pattern of current events and to see clearly through the haze of propaganda coming from all political sides.

I need skill to bring clarity to others.

And I must use my knowledge and skill to serve others, and exhort my peers to do the same, or the society built by my ancestors will fall to ruin, and I will one day find myself standing in the rubble only to look down and find the hammer and chisel in my own hands.

So, I’m currently diving deeper into my studies of history. I’m putting in extra effort to get my hands on old books in their original languages. I’m increasing the standard to which I hold my sources of news and information so that I can discern truth from lies.

This is shaping my work.

I don’t want to simply be another voice in self improvement, pop philosophy, pop psychology, and the “manosphere.”

I want to seek and share truth in service of the people of the future who are bound to suffer if we let our society erode in the present.

It has begun to earn me critics and enemies, but I have learned that conflict is the price of progress.

I just hope I can contribute to peace before any more blood is drawn.

Yeehamaste, folks 🤠

What I’m Listening To This Week

I’m still diving deep into classical music, recently by consuming full-length compositions in context. This week, I’ve been listening to Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky.

A Piece Of Art To Inspire You

In alignment with some of my recent writings about the decline of creativity, I want to start sharing great works of art which have caught my attention. I hope you will enjoy them as much as I do.

This week, I want to share the piece Saint Jerome Writing by Caravaggio.

Buy My Book

The Testimony of Jacob Cohen is a cosmic horror story about an archeologist on an Antarctic expedition who discovers a mysterious ziggurat that hides terrifying secrets from a forgotten past.

It draws inspiration from the narrative style of Dracula, the real-life Endurance expedition led by Ernest Shackleton, and Dionysian cult mysticism, along with modern astronomy, astrobiology, and mycology.

Helpful Links: Official Website | Latest Book | Podcast | YouTube | LinkedIn | X